‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ in 569 GIFs

March 28th, 2016

Deliberately setting out to test the rights and limitations of the Fair Use doctrine, digital producer and copywriter Jean-Baptiste Henri Franck Cyrille Marie Le Divelec (JB for short) has edited Stanley Kubrick’s 2-hour and 41-minute classic epic down to 569 animated GIFs. Permission from Kubrick’s estate was not requested. Instead, JB wants to make the point that since the GIFs are silent and and contain only 256 colors, this format should be protected from copyright infringement arguments by the Fair Use doctrine.

An interesting example of how malleable the transformative aspect of Fair Use can be. I’m curious to see if this soundless and subtitled version of 2001: A Space Odyssey will be contested or not. For now, you can watch it here.

No fees for Fair Use says foundation

March 9th, 2016

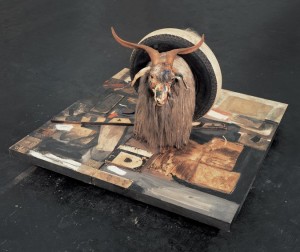

Late last month, The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation decided to drop all royalty fees, permissions, and license agreements for anyone who wants to reproduce the artist’s works under fair use. From the Foundations website: “We are pleased to announce a new Fair Use policy–the first to be adopted by an artist-endowed foundation–that will make images of Rauschenberg’s artwork more accesible to museums, scholars, artists, and the public.”

A both fair and important decision as Branden W. Joseph, Rauschenberg expert and professor of modern and contemporary art at Columbia University, points out: “To publish an academic book, it can cost several thousand to over $10,000 for images.” (NYT)

“Monogram,” by Robert Rauschenberg. A combine from 1955–59. Image from Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Judges unanimously side with ‘Dancing Baby’

September 15th, 2015

Remember the “Dancing Baby” lawsuit? It began back in 2007 when Stephanie Lenz uploaded a 29-second long video of her toddler dancing to the Prince song “Let’s go crazy” to YouTube. When Universal, Prince’s publishers, sent her a takedown notice Lenz refused and instead began, with the help of Electronic Frontier Foundation, a legal battle for fair use. Yesterday, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco ruled unanimously in favor of Lenz and the EFF and while doing so, the three-judge panel included a guideline strongly favoring fair use, ruling that “copyright holders like Universal must consider fair use before issuing takedown notices.” (NYT)

To require a case-by-case basis evaluation by rights holders and content users alike seems perfectly fair – a big win for fair use.

The take away: an important reminder from the experts

June 12th, 2015

By far, the most important thing I (re)learned at this year’s annual copyright conference at UCCS is that we, librarians and staff at academic institutions, should treat each and every copyright related question we get as a teaching opportunity. Several times during the conference, the highly esteemed featured speakers Dr. Kenneth D. Crews and Kevin Smith eloquently reminded the audience that only attorneys can and should dispense with legal advice. The rest of us, regardless of our positions, experiences, and titles at our individual institutions, share the role of educators, and rather than policing our communities, we are here to educate our patrons about copyright. What this means in more practical terms is that none of us should ever (allow ourselves to) be put in a position of making decisions about other people’s use of copyrighted material. Instead, our job is to teach and empower students, faculty, and staff to see themselves as both content creators and content consumers. As such, we all need to know how to make informed decisions, understand the importance of being able to formulate strong arguments in favor of our use of copyrighted materials, as well as to recognize when there is actual need to consult an attorney.

To paraphrase Dr. Crews, we should all end every conversation about copyright with the question: “Did you notice that I didn’t tell you what you should or shouldn’t do?”

Good copy(right) in the New Yorker

October 21st, 2014

In the most recent New Yorker magazine (October 20, 2014; also available online), staff writer Louis Menand deciphers not only the basics of American copyright law, but also some of the fundamental debates about it in “Crooner in Rights Spat.” This article is not only informative, it stands as a great potential access point to bring students and faculty up to speed on the issues. My biggest critique of the piece is that Menand has pulled the wool from my eyes and I now feel guilty providing links. I will, however, suppress my guilt and tell you that the article is available here: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/10/20/crooner-rights-spat

On the heels of this, the newyorker.com (online) yesterday published “Taking Pictures: A Way for Photographers to Protect Their Work,” by Betsy Morais. This brief profile of photographer and photojournalist Yunghi Kim illlustrates the many ways that photographers in particular (and, one might assume, visual artists more generally) must protect their rights to their work in the age of easy digital reproduction. An excellent article to share with students who are both content producers and content consumers. See http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/photographers-can-protect-work

Monkey see, monkey do

August 11th, 2014

On an expedition to Indonesia, British photographer David Slater had his camera stolen by a trigger-happy and photogenic macaque that – remarkably! – managed to take a phenomenal selfie. Among humans, whoever hits the shutter generally gets the copyright, but what happens if a monkey takes a photo? The Wikimedia Foundation maintains that the photo is in the public domain while Slater claims he owns copyright. What do the experts say? Here’s an analysis.

Are we Copyright First Responders?

July 15th, 2014

Thanks to Curtis Kendrick for this link from Harvard. Their Office of Scholarly Communication has a team of Copyright First Responders, which got me thinking. While I would very much like to wear a cape, and run around the library with a (c) emblazoned on my chest, Harvard’s Copyright First Responders are not individual superheros fighting the good copyright fight. They are purposefully developing a community of like-minded experts who are equally interested in copyright and in creative scholarship.

With the CUNY Copyright Committee, we have the rudiments of that community, but I puzzle over how we can take it to the next level — or if we should. Do we match Harvard’s call to “create a collaborative network of support among their peers involved with copyright issues, both locally and across the library, and serve as a resource for the Harvard [CUNY] community by answering copyright questions and sharing critical knowledge?”

How do we describe our mission as (c) at CUNY? Should we likewise be focused on collaboration and support?

Summer school for copyright, anyone?

June 20th, 2014

Coursera is offering a Copyright for Educators and Librarians MOOC from July 21-August 18. The course will be taught by Kevin Smith, Lisa A. Macklin and Anne Gilliland, all of whom are librarians and lawyers. Two of us at Hunter will be taking it — if you’re around and would like to form a study group, let us know!

– Stephanie Margolin & Malin Abrahamsson

mab0007@hunter.cuny.edu or smargo@hunter.cuny.edu

HathiTrust: an important ruling in favor of fair use

June 12th, 2014

In its decision Tuesday, a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the verdict from 2012, by Federal Judge Chin, in an important fair use ruling in the Authors Guild vs. HathiTrust case. Ruled “a quintessentially transformative use” by the court, HathiTrust’s massive scanning project could have a potentially far-reaching impact on making works accessible for the print disabled. Read more here.

Marx on May Day and other copyright news this week

May 2nd, 2014

Whose work better to be freely available than Marx? And yet on May 1 2014 (yes, May Day) the Marxist Internet Archive received a cease and desist from a small, leftist publisher, Lawrence & Wishart, who owns the copyright to a 50-volume English language edition of Marx & Engels’ writing. Read the first installment of this David vs. David battle in the New York Times. More is surely soon to come.

And for our own intellectual property rights, this recent New York Times dispatch on Terms of Service agreements among various popular social platforms. Do you know what rights you have given away?